The Process of Making Sake

The Process of Making Sake

The Process of Making Sake

Sake is made through a fermentation process using rice, koji rice, and water.

The ingredients themselves are simple,

but the process is extremely complicated compared to that for making wine or beer.

Here we will introduce the process behind the ever-familiar drink of sake.

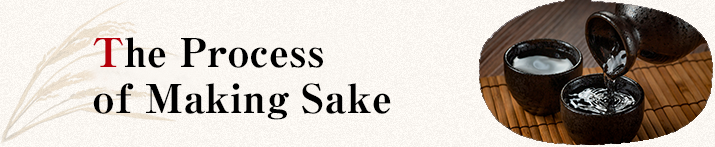

Polishing, Washing, and Steaming Rice

A specific type of rice, sake brewer’s rice, is used

in the making of sake. The sake brewing process

starts with milling, or scraping off the outer husk

of the rice, and polishing. This is done to remove

the proteins and fats that exist in this outer shell,

an important step to creating delicious sake without

off-putting flavors that would ruin the sake’s

taste. Rice for general consumption is typically

only polished to remove about 10% of the outer

husk, but rice intended for sake brewing must be

polished to about 30%, and rice for Daiginjo sake

is polished to 50% or higher.

After it is polished, the rice is rinsed clean, then allowed

to absorb a certain amount of water. Then,

the steaming process is begun using a steaming

vat. Because the rice is cooked through steam,

the grains are kept firm and distinctly separated.

This is important in the making of sake, and sticky

rice is unsuited for sake production. Once the

steaming process is finished, the rice is divided

into portions designated for koji, shubo, and

moromi. About 15-25% of the steamed rice is

used for koji.

Making Koji Rice,Shubo, and Moromi

One of the important steps that determines the quality of sake is

the koji rice production. Steamed rice is cooled, spores of koji

mold are sprinkled across the surface, and the rice is kept at a regulated

temperature for about 2 days. The koji is ready when a

white substance called “Haze” spreads across the surface of the

rice. Next up is the production of the shubo (yeast mash starter),

the true basis of sake. Water, koji rice, and steamed rice are put

into a tank together in order to foster yeast growth. Once the

quantity of yeast has increased enough, the making of moromi

begins. Steamed rice, koji rice, water, and the shubo are placed

into a fermentation tank to be prepared. Not all of the ingredients

are added at once in this step ‒ instead, they are prepared in multiple

batches. This is typically called the “Sandan jikomi,” or

“three-stage mashing,” because it is done in three steps.

Pressing and Straining

Joso is the process of pressing the moromi, separating it into sake and sake kasu (lees). The pressed sake is then filtered to remove impurities that can cause odors. Once that is done, it goes through a process called “Hi-ire,” low-temperature sterilization or pasteurization, to stabilized storage quality before storage. The sake is bottled when it is ready to be shipped out. Sake that does not undergo hi-ire is called “Namazake.”

Different Types of Sake and Choosing Between Them

Refined sake can generally be classified

into four types depending on factors

such as ingredients and rice polishing ratio: Ginjo-shu, Junmai-shu,

Honjozo-shu, and Futsuu-shu. Of these, Ginjo-shu,

Junmai-shu, and Honjozo-shu are Special Designation

Sake (Tokutei meisho-shu) that can then be roughly classified into 8 types.

| Special Designation Sake |

Ingredients Used |

Rice Polishing Ratio | Ratio of Koji Rice Used |

Flavor and Other Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginjo-shu | Rice, koji rice, brewer's alcohol |

60% or lower | 15% or higher | Ginjo-zukuri, characteristic flavor,good color and clarity |

| Daiginjo-shu | Rice, koji rice, brewer's alcohol |

50% or lower | 15% or higher | Ginjo-zukuri, characteristic flavor,and particularly good color and clarity |

| Junmai-shu | Rice, koji rice | 15% or higher | Good flavor, color, and clarity | |

| Junmai Ginjo-shu |

Rice, koji rice | 60% or lower | 15% or higher | Ginjo-zukuri, characteristic flavor,good color and clarity |

| Junmai Daiginjo-shu |

Rice, koji rice | 50% or lower | 15% or higher | Ginjo-zukuri, characteristic flavor,and particularly good color and clarity |

| Special Junmai-shu |

Rice, koji rice | 60% or lower, or special production method (requires explanation) |

15% or higher | Particularly good flavor, color, and clarity |

| Honjozo-shu | Rice, koji rice, brewer's alcohol |

70% or lower | 15% or higher | Good flavor, color, and clarity |

| Special Honjozo-shu |

Rice, koji rice, brewer's alcohol |

60% or lower, or special production method (requires explanation) |

15% or higher | Good flavor, color, and clarity |

Sake o Shiori(2018 Edition),from National Tax Agency

How to Read Sake Labels

Sake’s label shows its ingredients, alcohol

content, and other information,

as well as its sake meter value (SMV)

and acidity, so be sure to check the

label when choosing sake. It’s no

easy matter to judge sake by the label

alone, though, so be sure to sample

different options and find a balance

that suits your personal tastes.

Things to Check

- Rice Polishing Ratio

- The ratio of polished to original unpolished rice by weight. A rice polishing rate of 60% means that 40% of the original unpolished rice’s husk has been milled off.

- Sake Meter Value (SMV)

- A measure of the sweetness and alcohol levels of sake. The higher into positive values, the dryer (less sugar) the sake is.

- Acidity

- Represents the sour acidic flavors in sake. Sake with high Acidity acidity has a sharp and dry taste.

- Level of Amino Acids

- Sake with high levels of amino acids has stronger umami flavors, while lower levels result in smoother flavors.

Flavors and Types of Sake

-

Aromatic Types

Varieties such as daiginjo-shu and ginjo-shu feature lovely, clean fruity or floral aromas. They are moderately sweet with a somewhat rounded flavor, refreshing and well-balanced. They are best served at 10 to 16 ℃. Also can be served at “nurukan” temperatures, warmed to around 40℃.

-

Light and Smooth Types

Light and dry types of sake are characterized by mild, unobtrusive aromas and a refreshing flavor. They are best served at low temperatures, around 6 to 10℃. They are also well-suited for serving in wine glasses.

-

Aged Types

Aged sake is characterized by its powerful and complex spice and fruit aromas. They are quite sweet, and their mellow flavors harmonize with the well-rounded acidity. Can be served at a wide range of temperatures, such as 7 to 25℃.

-

Types with Body

Types of sake with body have woody or milky aromas, with well-rounded flavors that combine sweetness, tartness, and a pleasant bitterness. They can be served between 10 to 45 ℃, and their flavors change depending on the serving temperature.

Source: Japan Sake & Shochu Makers Association

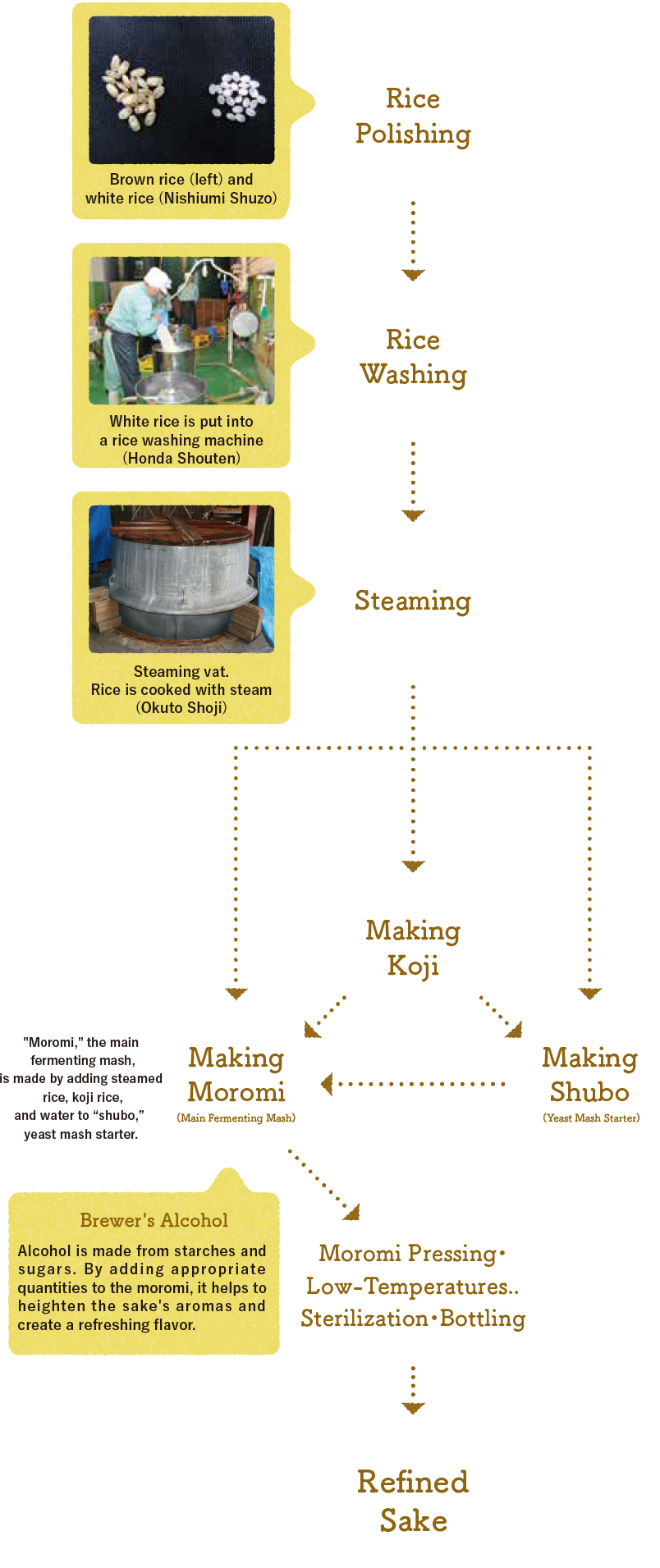

Enjoying Different Flavors by Temperature

A major point of sake is that its flavors and aromas change when it is warmed or chilled.

Source: Japan Sake & Shochu Makers Association

New Way to Drink Cold Sake

Here we will introduce how to drink cold sake,

which is gaining popularity among younger people.

- ●Samurai Rock

- A slice of lemon is placed in drinks served on the rocks, but with Samurai Rock lime is used instead. Sake typically is said to lack in acidity, so it is often supplemented with citric acid, and lime’s flavor is particularly suitable to sake.

- ●Mizore-zake

- Freezing sake by slowly lowering its temperature results in a “supercooled” state. Due to its alcohol content, sake remains liquid at even -10℃ and below, but if you pour sake that is this cold into another container, the liquid crystalizes from the impact, changing it into a slush-like state.

- ●Sake Sorbet

- Sake sorbet is frozen sake. Sake is poured into a glass, wrapped, and placed into a freezer. If stirred occasionally, after 4-5 hours it will freeze into a sorbet-like state. It can be drank in this state, or spooned out for eating.

- ●Kan Rock

- Kan rock sake is hot sake served over ice. If you shake the glass slightly, the sake cools instantly, leading to a lighter flavor than typical on the rock sake.

Source: Japan Sake & Shochu Makers Association